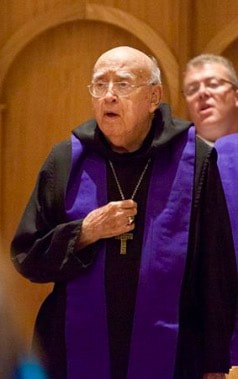

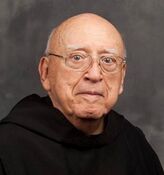

Father Bonaventure Knaebel, OSB

Monk, priest, and former archabbot of Saint Meinrad Archabbey, died in the monastery infirmary on Friday, January 22, 2021. He was 102.

Fr. Bonaventure was born in New Albany, IN, on September 6, 1918, to Vincent Joseph and Mary Elizabeth (Moore) Knaebel. He was given the name James Merton at his baptism. After completing his elementary education at Holy Trinity in New Albany, he entered the high school at Saint Meinrad in 1931.

He began college studies at Saint Meinrad in 1935, entered the novitiate in 1937, and professed his simple vows on August 6, 1938. He completed college studies in 1940 and began studying for the priesthood. He professed solemn vows on August 6, 1941, and was ordained to the priesthood on June 5, 1943.

Immediately after ordination, Fr. Bonaventure began graduate studies in mathematics at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., earning an MS degree in 1946.

Returning to Saint Meinrad, he taught in Saint Meinrad High School and College from 1946 to 1955, serving also as assistant spiritual director in the School of Theology. During these years, he also was assistant manager of The Grail and of the Abbey Press, and he studied advanced mathematics for three summers at the University of Pittsburgh.

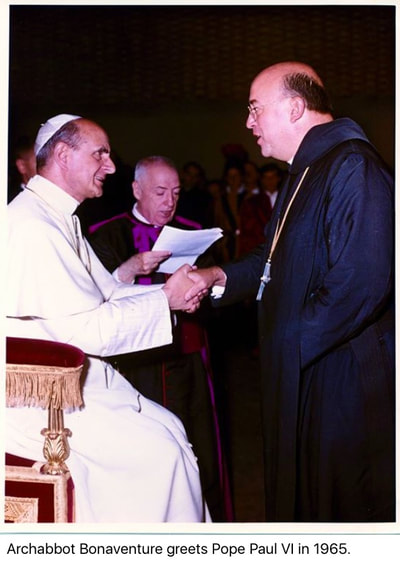

Fr. Bonaventure was elected coadjutor abbot on June 3, 1955, to succeed Archabbot Ignatius Esser, and he was blessed as the fifth abbot and second archabbot of Saint Meinrad on August 31, 1955. He was the first Hoosier native to lead the monastery and, at 36, one of the youngest Benedictine abbots.

Under his leadership, Saint Meinrad Archabbey saw the construction of its first guest house and of St. Bede Hall, which provided a residence hall for college seminarians, science laboratories, and music practice rooms until the closing of the College in 1998.

He also oversaw the foundation of two monastic houses – St. Charles Priory in Oceanside, CA, (now Prince of Peace Abbey) and St. Benedict Priory in Huaraz, Peru (which ceased operation in 1984). He also formed a Development Program Committee and reorganized the Abbey Press.

Saint Meinrad School of Theology and the College of Liberal Arts achieved accreditation by the North Central Association under his direction, the Board of Trustees was completely revised, and a Board of Overseers consisting of diocesan priests and laity was organized. Fr. Bonaventure resigned from the Office of Archabbot on June 3, 1966, having served 11 years.

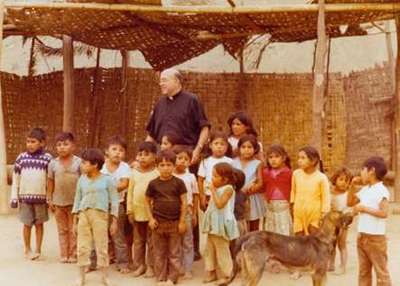

Fr. Bonaventure then began missionary work at Saint Meinrad’s foundation in Peru, South America. After eight years, he returned to the United States to serve from Saint Meinrad as mission procurator for the Huaraz foundation, work he continued for five years. In 1979, he accepted an assignment as pastor of Sacred Heart Parish in Jeffersonville, IN, for two years, after which he spent five years as pastor of St. Michael Parish in Charlestown, IN.

In 1986, the Abbot President of the Swiss-American Congregation sought his experience as an abbot and as a South American missionary and asked him to serve as administrator of Monasterio Benedictino in Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico, which he did for two years.

Returning to this country in 1989, he served successive assignments as chaplain of St. Paul’s Hermitage, Beech Grove, IN, (six years); administrator of Corpus Christi Abbey, Sandia, TX, (two years); and administrator of St. Michael Parish, Bradford, IN (six years).

Fr. Bonaventure returned to the abbey in 2003. He was 85 years old, but he assisted in the Development Office and occasionally provided assistance in local parishes. For some years, he also regularly presided at Mass in the Infirmary Chapel and continued to preside at Spanish-language Masses at St. Mary’s Parish in Huntingburg, IN.

At the time of his death, he was the senior in age, profession, and ordination in the Swiss-American Benedictine Congregation. He was in the 82nd year of his monastic profession and the 77th year of priesthood.

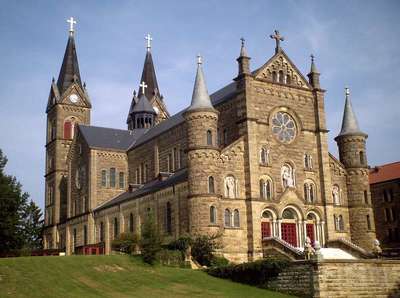

The Office of the Dead will be prayed at 7 p.m. Central Time on Tuesday, January 26, in the Archabbey Church. The funeral liturgy will be celebrated at 10 a.m. Central on Wednesday, January 27, in the Archabbey Church. Burial will follow in the Archabbey Cemetery.

Monk, priest, and former archabbot of Saint Meinrad Archabbey, died in the monastery infirmary on Friday, January 22, 2021. He was 102.

Fr. Bonaventure was born in New Albany, IN, on September 6, 1918, to Vincent Joseph and Mary Elizabeth (Moore) Knaebel. He was given the name James Merton at his baptism. After completing his elementary education at Holy Trinity in New Albany, he entered the high school at Saint Meinrad in 1931.

He began college studies at Saint Meinrad in 1935, entered the novitiate in 1937, and professed his simple vows on August 6, 1938. He completed college studies in 1940 and began studying for the priesthood. He professed solemn vows on August 6, 1941, and was ordained to the priesthood on June 5, 1943.

Immediately after ordination, Fr. Bonaventure began graduate studies in mathematics at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., earning an MS degree in 1946.

Returning to Saint Meinrad, he taught in Saint Meinrad High School and College from 1946 to 1955, serving also as assistant spiritual director in the School of Theology. During these years, he also was assistant manager of The Grail and of the Abbey Press, and he studied advanced mathematics for three summers at the University of Pittsburgh.

Fr. Bonaventure was elected coadjutor abbot on June 3, 1955, to succeed Archabbot Ignatius Esser, and he was blessed as the fifth abbot and second archabbot of Saint Meinrad on August 31, 1955. He was the first Hoosier native to lead the monastery and, at 36, one of the youngest Benedictine abbots.

Under his leadership, Saint Meinrad Archabbey saw the construction of its first guest house and of St. Bede Hall, which provided a residence hall for college seminarians, science laboratories, and music practice rooms until the closing of the College in 1998.

He also oversaw the foundation of two monastic houses – St. Charles Priory in Oceanside, CA, (now Prince of Peace Abbey) and St. Benedict Priory in Huaraz, Peru (which ceased operation in 1984). He also formed a Development Program Committee and reorganized the Abbey Press.

Saint Meinrad School of Theology and the College of Liberal Arts achieved accreditation by the North Central Association under his direction, the Board of Trustees was completely revised, and a Board of Overseers consisting of diocesan priests and laity was organized. Fr. Bonaventure resigned from the Office of Archabbot on June 3, 1966, having served 11 years.

Fr. Bonaventure then began missionary work at Saint Meinrad’s foundation in Peru, South America. After eight years, he returned to the United States to serve from Saint Meinrad as mission procurator for the Huaraz foundation, work he continued for five years. In 1979, he accepted an assignment as pastor of Sacred Heart Parish in Jeffersonville, IN, for two years, after which he spent five years as pastor of St. Michael Parish in Charlestown, IN.

In 1986, the Abbot President of the Swiss-American Congregation sought his experience as an abbot and as a South American missionary and asked him to serve as administrator of Monasterio Benedictino in Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico, which he did for two years.

Returning to this country in 1989, he served successive assignments as chaplain of St. Paul’s Hermitage, Beech Grove, IN, (six years); administrator of Corpus Christi Abbey, Sandia, TX, (two years); and administrator of St. Michael Parish, Bradford, IN (six years).

Fr. Bonaventure returned to the abbey in 2003. He was 85 years old, but he assisted in the Development Office and occasionally provided assistance in local parishes. For some years, he also regularly presided at Mass in the Infirmary Chapel and continued to preside at Spanish-language Masses at St. Mary’s Parish in Huntingburg, IN.

At the time of his death, he was the senior in age, profession, and ordination in the Swiss-American Benedictine Congregation. He was in the 82nd year of his monastic profession and the 77th year of priesthood.

The Office of the Dead will be prayed at 7 p.m. Central Time on Tuesday, January 26, in the Archabbey Church. The funeral liturgy will be celebrated at 10 a.m. Central on Wednesday, January 27, in the Archabbey Church. Burial will follow in the Archabbey Cemetery.

Happy 100th Birthday!

9-6-1918 – 9-6-2018

Retired Benedictine Archabbot marks 75 years as a priest, 80 as a monk,

48 as a Knight of Columbus in New Albany, Indiana at Cardinal Ritter Council #1221

& Father Badin Assembly #0244.

Cardinal Ritter Council #1221 has 4 living generations of Knaebel's in it's ranks.

Vivat Jesus!

RRV Bonaventure M. Knaebel, OSB celebrated his first Mass as a priest in 1943 at the height of World War II.

99-year-old monk says,

‘First, love God’

By OLIVIA INGLE / April 4, 2018

[email protected]

ST. MEINRAD — Father Bonaventure Knaebel’s favorite chapter of the Rule of St. Benedict is Chapter 72.

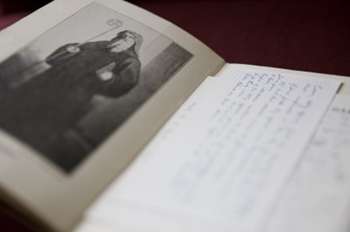

The former archabbot and 99-year-old, spectacled monk scoots his wheelchair to a bookshelf in his room in the Saint Meinrad Archabbey infirmary, grabs the small, brown hardback book and opens its weathered pages. Handwritten notes, in Latin, fall to the floor.

The Rule is a basic guide to living life in the Benedictine community and was written by St. Benedict, who lived from A.D. 480 to 550. Fr. Bonaventure’s edition was published in 1937, and he’s had the book ever since. It’s something he treasures.

“It’s about understanding one another,” he says of Chapter 72, which encourages those in the vocation to honor and be obedient to one another, all in the name of Christ.

“Don’t become alienated with one another, be willing to overlook some of the natural tendencies,” Fr. Bonaventure says of his interpretation of the chapter he’s clung to through the years.

This year is a big one for him, as he will celebrate his 75th jubilee (anniversary) as a priest, 80th as a monk and will turn 100 years old on Sept. 6.

“It’s kind of special,” he says of the jubilees. “All priests like to reach 50 (50th jubilee) especially.”

How does he feel about his 75th?

“It happens if you live that long,” he replies matter-of-factly.

Fr. Bonaventure is the oldest living monk in age, profession and ordination in the Swiss-American Benedictine Congregation, a network of autonomous monastic houses — including Saint Meinrad Archabbey — in the United States, Canada and Central America.

He believes good genes got him to 99. A first cousin — Fr. Bonaventure calls him a “double first cousin” since they were first cousins on both sides of the family — died at 99 after complications following hip surgery.

“That’s the closest I have to longevity,” Fr. Bonaventure says.

He admits prayer has led him far in life, and without it, he says he probably wouldn’t be alive.

“I would have drank too much or something,” he says. “It’s (prayer) the only thing I have that’s worthwhile.”

Fr. Bonaventure was born Sept. 6, 1918, and given the name Merton James. He grew up the oldest of three brothers in New Albany. He first took interest in the church in sixth grade when he told his parents he wanted to be a server at Mass. Since that required him to attend morning Mass daily, his mother bought him an alarm clock and he was responsible to get there on his own, a mile-and-a-half walk.

Then, in seventh grade, a newly ordained priest spoke to his class. The priest asked for a show of hands of who would like to be president of the United States. Two hands shot up. Then, the priest asked, “Who thinks they might like to be a priest?”

Fr. Bonaventure raised his hand. It was the first time he remembers ever considering the vocation.

After he finished eighth grade, the assistant pastor of his parish drove him and another boy to St. Meinrad to enroll in classes. Fr. Bonaventure was 13 when he entered minor seminary school in 1931. He graduated in 1935. In 1940 he received a bachelor’s degree from St. Meinrad and in 1944, a theology degree from the school. In 1946, he earned a master’s degree from the Catholic University of America and then studied mathematics for several summers at the University of Pittsburgh.

Fr. Bonaventure joined the monastery as a novice in July 1937 and made his first profession as a monk in August 1938. He was or-dained a priest, June 1943.

In 1955, he was elected archabbot of the Saint Meinrad Archabbey community at age 36; he’s still one of the youngest archabbots — a leader of an archabbey of monks who is elected by his peers — to have led at St. Meinrad. (He’s tied with St. Meinrad’s first abbot, Martin Marty, who also took the position when he was 36.)

Fr. Bonaventure says that as archabbot, he was “in charge of the physical plans and the liturgical life of the community.” He did things like appoint pastors at various parishes and assign monks — there were 197 at the time; 80 now — and priests to various duties at the archabbey, duties such as teaching, baking and cooking, and tending to the abbey’s farm.

“My favorite thing was seeing the community grow and thrive, the studies of individuals and their accomplishments,” Fr. Bonaventure says about his 11 years as archabbot. “They worked hard.”

He admits that being archabbot was in no way an easy job.

“It was difficult, I have to say that,” he says. “I had enough joys, but plenty of difficulties, also. I never knew what would happen next.”

During his tenure as archabbot, the monastery got its first guest house and better water and sewage treatment systems. He also helped establish a new foundation in Huaraz, Peru, as well as Prince of Peace Abbey in Oceanside, California, in 1958.

When asked what kind of leader he was, Fr. Bonaventure humbly says, “I’m sure I wasn’t considered charismatic. I was just plodding along.”

He resigned as archabbot in 1966.

Throughout his years as a monk, Fr. Bonaventure has had a variety of duties in addition to being archabbot. He was a teacher, a missionary in Peru and helped lead monasteries in the interim in Mexico and the U.S. He also had stints leading several parishes before returning to St. Meinrad where he has helped with projects in the archabbey’s development office.

Throughout all of his assignments, Fr. Bonaventure has always held true to the vows of a Benedictine monk — vows of obedience, stability and fidelity to the monastic way of life.

He does quite a bit of Scripture study on the kingdom of God, although not nearly as much as he’d like because of vision problems. He says he spends most of his day praying the Divine Office, which he listens to on tape.

He attends coffee break with other monks at 10 o’clock every morning and attends Mass in the infirmary at 11:15 a.m., followed by lunch in the infirmary dining room. His afternoon includes a nap and some free time. Sometimes he prays or listens to audiobooks.

He also has an iPad and catches up with friends and family on Facebook. On March 27, he said he had just sent his niece a message on Facebook the day before wishing her a happy birthday.

After 5 o’clock, he likes to watch the local news, especially the weather forecast. He used to watch Carol Burnett shows, but says he now watches a lot of CNN. He once enjoyed long walks, but is now confined to a wheelchair.

Just like his interests, Fr. Bonaventure has noticed several changes in the Catholic faith over the course of his eight decades as a monk, including the lack of “a greater interest and attention to the life of Sunday Mass.” It didn’t used to be that way, he says.

“My grandma had 10 children and her husband died from typhoid fever when she was pregnant with the youngest,” he says. “She got the kids in the wagon and got the kids to Mass a couple miles on Sunday. I don’t remember a Sunday my father didn’t take me and my brothers to Sunday Mass.”

He longs for more people to follow St. Benedict’s teaching’s.

“St. Benedict starts out with things to observe,” he says. “First, love God with all your heart and strength. Love your neighbors as you are. It has to get simpler more than complicated in life.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

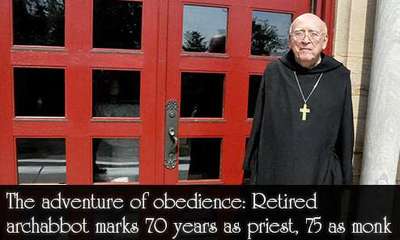

THE ADVENTURE OF OBEDIENCE...

By Sean Gallagher

August 16, 2013

ST. MEINRAD—“When you make the vow of obedience, you don’t know what’s going to happen.”

That was how retired Benedictine Arch-abbot Bonaventure Knaebel of Saint Meinrad Archabbey in St. Meinrad succinctly summarized his 75 (80) years as a monk and 70 (75) years as a priest.

Born in 1918 in New Albany, he professed his monastic vows during the Great Depression in 1938, was ordained a priest at the height of World War II in 1943 and elected Archabbot of Saint Meinrad in 1955, eventually resigning from the office in 1966.

During his 75 (80) years as a monk, Archabbot Bonaventure has also served as a seminary instructor, a missionary in Peru, temporary administrator of monasteries in Mexico and the United States, chaplain of St. Paul Hermitage in Beech Grove and pastor or administrator of three parishes in the Archdiocese of Indianapolis.

It was to all of these places and these wide and varied ministry experiences that Arch-abbot Bonaventure’s fidelity to his vow of obedience led him.

Benedictine Arch-abbot Justin DuVall, Saint Meinrad’s then current leader, admires his predecessor’s dedication to obedience.

“He is one of the most obedient monks, really, in a way, that I know,” Arch-abbot Justin said. “He’s the kind of guy who, as abbot or when I was prior, I could ask him, ‘Could you do this?’ or ‘I need this to be done,’ and he’d say ‘Certainly.’ He would do it.”

Archabbot Bonaventure’s adventure of obedience started while growing up in New Albany.

Discerning his calling early on

The Arch-abbot showed an interest in the priesthood when he was in the seventh grade at the former Holy Trinity School in New Albany after a man from Holy Trinity Parish had been ordained a priest.

He explored that desire in part by serving at daily Mass at the parish—a Mass that started at 6 a.m. In response to this desire to be an altar server, his mother bought him an alarm clock.

“That was her way of seeing how true the idea was,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said. “Was it just a fleeting thing or is it steady? I must have walked there. It was more than a mile away. If there was snow on the ground, I could take a street car.”

When he completed eighth grade, he decided to enter the minor seminary at Saint Meinrad. Once he got there, though, he soon yearned to be back home. A monk on the seminary staff helped him through this difficult time.

“The main thing that he did that was a lifesaver was he got in touch with my folks, and told them not to come down to visit until the second Sunday in October … ,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said. “If they had come like two weeks after I got here, I would have gotten into the car and gone home with them.”

He was impressed enough by the monks and by reading a biography of St. Benedict that the next year he declared his intention to join the monastery when he was old enough.

From math teacher to Arch-abbot

Early on, his life in the monastery was much like many other young monks—receiving formation in the monastic life and for the priesthood in the seminary.

Ordained in 1943, he asked Benedictine Arch-abbot Ignatius Esser if he could serve as a military chaplain.

“But we already had six men as chaplains at the time,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure recalled. “So he didn’t take me up on it.”

He put his vow of obedience into action in accepting that decision. It was soon tested again when Benedictine Father Theodore Heck, then rector of the seminary, asked him to study mathematics in graduate school, even though his last math class was geometry as a high school sophomore.

“He didn’t ask me if I was interested in it,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said.

He earned a master’s degree in the field and nearly a doctorate, later teaching math in the minor seminary for eight years.

In 1955, Arch-abbot Ignatius announced his intention to resign after having led Saint Meinrad Archabbey for 25 years.

More than 100 monks participated in the election to choose his successor. Many ballots were cast before a monk received enough votes to be elected. As each ballot was counted, the name of the monk on it was announced.

During the counting of the last ballot, Arch-abbot Bonaventure, then only 38, said he “had butterflies” as he kept hearing his name called.

Much like a papal election, when he reached a majority on the ballots, he was asked if he accepted the election.

Arch-abbot Bonaventure consented “with the help of God” to become the leader of the monastery, treating the will of his fellow monks as another test of his vow of obedience.

“Certainly, it was expected of you at that time that if you were elected that you would accept it,” he said.

The challenge of leadership

The responsibilities that Arch-abbot Bonaventure took on after his election were wide and varied.

He initiated various projects as Arch-abbot, including the construction of the monastery’s first guest house, a water purification plant and two sewage ponds.

He laughed as he said that this last project was “the only successful thing I did.

“The guest house has been torn down. And the water [purification] plant is now the pottery shop.”

He and the monastic community also established two new monasteries during his tenure—Prince of Peace Abbey in Oceanside, Calif., and San Benito Priory in Huaraz, Peru.

The latter came in response to the call of Blessed John XXIII in 1961 to religious communities in the United States to send 10 percent of their members to minister in Central and South America within 10 years.

Arch-abbot Bonaventure and the monks of Saint Meinrad obeyed and established their foothold in Peru less than a year after the pope laid down the challenge. In addition to the priory, the monks ministering there also operated a minor seminary in Huaraz, which is located deep in the mountains of Peru.

While being responsible for various brick and mortar projects, Arch-abbot Bonaventure was also given the charge of caring for the souls of nearly 200 monks.

One of them was Benedictine Father Meinrad Brune, who became a novice the same year that Arch-abbot Bonaventure was elected.

One day, Arch-abbot Bonaventure heard Father Meinrad complaining about another monk. He later called him to his office and simply asked him to read an article on what he had done.

“He didn’t even discuss it with me,” Father Meinrad said. “It was a somewhat indirect way to give me correction. But he did it in a very thoughtful way. It was a very good article. And I knew right away exactly what he was referring to. So I thanked him for it, and that was all that was said.”

The Second Vatican Council also took place while Arch-abbot Bonaventure was the monastery’s leader. He was obedient to the will of the bishops at the council by starting the process to make the changes called for at Vatican II in the celebration of Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours (also known as the Divine Office or simply the Office).

“We did make some appropriate adjustments,” he said. “While the last section of the council was going on, we set up a liturgical committee and they started celebrating the Office in English as an experiment in the chapter room [a special meeting room in the monastery] while we were still doing it in Latin [in the Archabbey Church].”

The years that Arch-abbot Bonaventure served as leader of Saint Meinrad, however, included some trials as well. Nearly 50 years later, he still only talked about them in a measured manner.

“One of the older priests told someone, then I heard it, that Arch-abbot Ignatius enjoyed being abbot and Bonaventure doesn’t enjoy it that much,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said. “That was the impression that the older fellow had gotten. I think, in a sense, that must have been true.

“At the time [of my resignation in 1966], I said that Father Abbot Ignatius served for 25 years, but 11 years of what we’ve been having is like 25.”

Arch-abbot Justin reflected on the challenging time in which Arch-abbot Bonaventure served as leader of Saint Meinrad.

“You can’t be the abbot in another era than your own,” Arch-abbot Justin said. “When he was elected in 1955, who could have foreseen the council and the aftermath of that? And that’s when he was abbot. Those were challenging times not just for him or for Saint Meinrad, but for the Church at large.”

Life as missionary

Arch-abbot Bonaventure stepped down as leader of Saint Meinrad in June 1966. By November of that year, he was studying Spanish in preparation to serve in Peru.

At first, he served as the rector of the minor seminary.

His ministry there changed dramatically, however, in 1970 when an earthquake struck the country. Some 70,000 people died in the quake, including Benedictine Father Bede Jamieson, prior of San Benito Priory at the time.

When the quake occurred, Arch-abbot Bonaventure was walking with a local bishop just prior to the blessing of a cornerstone for a new convent for a community of religious sisters.

“There were garden walls along there,” he said. “Then the earthquake came. Luckily, those walls didn’t fall down. If we had been walking in a narrow street in front of houses like they were in Huaraz, the fronts of the buildings would have fallen and hit people in the streets.”

Instead of assisting in relief work in Peru, Arch-abbot Bonaventure was asked to return to the United States to make mission appeals in parishes across the country. He later did this ministry full time from 1974-79.

Leading parishes, other monasteries

Beginning in the late 1970s, Arch-abbot Bonaventure began serving in a series of parish and monastic assignments, serving 17 years in parishes and at the St. Paul Hermitage in the archdiocese, and as temporary administrator in monasteries in Mexico, Wisconsin and Texas.

While in Mexico, he also tackled a good amount of parish ministry.

“I had to revive my Spanish. It was interesting work,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said. “I had plenty of Masses. I think I had three Holy Thursday Masses and three Easter Vigils [during one Holy Week].”

His last parish assignment before retiring to the monastery was at St. Michael Parish in Bradford. In 1997, its pastor, Father Bernard Koopman, died suddenly and Arch-abbot Bonaventure, 77 at the time, was asked to fill in for two and a half months until a pastor could be appointed.

He obeyed, thinking he would return to the monastery in short order. He ended up staying there for six years.

John Jacobi, St. Michael’s director of religious education while Arch-abbot Bonaventure led the parish, continues in that position today.

“He had a lot of energy,” Jacobi said. “He showed up at anything—youth events, deanery events and things like that. Being able to watch him as a younger person kept me moving. It was his love of the Church, his love of ministry what sustained him.”

Arch-abbot Bonaventure also helped Jacobi grow in his ministry.

“I think he was really good at knowing when to listen and when to put his two cents in,” Jacobi said. “I think he taught me how to be a good parish minister, how to approach people where they are. He was just really good at that.”

Arch-abbot Bonaventure stepped down from leading St. Michael Parish because of health problems. In the past 10 years, he has had both of his knees replaced and dealt with a liver ailment.

Today however, at 94, he continues periodically to celebrate Mass in Spanish at St. Mary Parish in Huntingburg, Ind., in the Evansville Diocese, and assists in projects in Saint Meinrad’s development office.

When asked to give words of encouragement to men considering life as a Benedictine monk, Arch-abbot Bonaventure spoke about the purpose of his adventure of obedience—growing closer to God.

“I’m not sure that you would have any of the experiences that I’ve had, but it is a fulfilling life,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said. “It does help you to do what the Rule [of St. Benedict] says, to seek God.”

‘First, love God’

By OLIVIA INGLE / April 4, 2018

[email protected]

ST. MEINRAD — Father Bonaventure Knaebel’s favorite chapter of the Rule of St. Benedict is Chapter 72.

The former archabbot and 99-year-old, spectacled monk scoots his wheelchair to a bookshelf in his room in the Saint Meinrad Archabbey infirmary, grabs the small, brown hardback book and opens its weathered pages. Handwritten notes, in Latin, fall to the floor.

The Rule is a basic guide to living life in the Benedictine community and was written by St. Benedict, who lived from A.D. 480 to 550. Fr. Bonaventure’s edition was published in 1937, and he’s had the book ever since. It’s something he treasures.

“It’s about understanding one another,” he says of Chapter 72, which encourages those in the vocation to honor and be obedient to one another, all in the name of Christ.

“Don’t become alienated with one another, be willing to overlook some of the natural tendencies,” Fr. Bonaventure says of his interpretation of the chapter he’s clung to through the years.

This year is a big one for him, as he will celebrate his 75th jubilee (anniversary) as a priest, 80th as a monk and will turn 100 years old on Sept. 6.

“It’s kind of special,” he says of the jubilees. “All priests like to reach 50 (50th jubilee) especially.”

How does he feel about his 75th?

“It happens if you live that long,” he replies matter-of-factly.

Fr. Bonaventure is the oldest living monk in age, profession and ordination in the Swiss-American Benedictine Congregation, a network of autonomous monastic houses — including Saint Meinrad Archabbey — in the United States, Canada and Central America.

He believes good genes got him to 99. A first cousin — Fr. Bonaventure calls him a “double first cousin” since they were first cousins on both sides of the family — died at 99 after complications following hip surgery.

“That’s the closest I have to longevity,” Fr. Bonaventure says.

He admits prayer has led him far in life, and without it, he says he probably wouldn’t be alive.

“I would have drank too much or something,” he says. “It’s (prayer) the only thing I have that’s worthwhile.”

Fr. Bonaventure was born Sept. 6, 1918, and given the name Merton James. He grew up the oldest of three brothers in New Albany. He first took interest in the church in sixth grade when he told his parents he wanted to be a server at Mass. Since that required him to attend morning Mass daily, his mother bought him an alarm clock and he was responsible to get there on his own, a mile-and-a-half walk.

Then, in seventh grade, a newly ordained priest spoke to his class. The priest asked for a show of hands of who would like to be president of the United States. Two hands shot up. Then, the priest asked, “Who thinks they might like to be a priest?”

Fr. Bonaventure raised his hand. It was the first time he remembers ever considering the vocation.

After he finished eighth grade, the assistant pastor of his parish drove him and another boy to St. Meinrad to enroll in classes. Fr. Bonaventure was 13 when he entered minor seminary school in 1931. He graduated in 1935. In 1940 he received a bachelor’s degree from St. Meinrad and in 1944, a theology degree from the school. In 1946, he earned a master’s degree from the Catholic University of America and then studied mathematics for several summers at the University of Pittsburgh.

Fr. Bonaventure joined the monastery as a novice in July 1937 and made his first profession as a monk in August 1938. He was or-dained a priest, June 1943.

In 1955, he was elected archabbot of the Saint Meinrad Archabbey community at age 36; he’s still one of the youngest archabbots — a leader of an archabbey of monks who is elected by his peers — to have led at St. Meinrad. (He’s tied with St. Meinrad’s first abbot, Martin Marty, who also took the position when he was 36.)

Fr. Bonaventure says that as archabbot, he was “in charge of the physical plans and the liturgical life of the community.” He did things like appoint pastors at various parishes and assign monks — there were 197 at the time; 80 now — and priests to various duties at the archabbey, duties such as teaching, baking and cooking, and tending to the abbey’s farm.

“My favorite thing was seeing the community grow and thrive, the studies of individuals and their accomplishments,” Fr. Bonaventure says about his 11 years as archabbot. “They worked hard.”

He admits that being archabbot was in no way an easy job.

“It was difficult, I have to say that,” he says. “I had enough joys, but plenty of difficulties, also. I never knew what would happen next.”

During his tenure as archabbot, the monastery got its first guest house and better water and sewage treatment systems. He also helped establish a new foundation in Huaraz, Peru, as well as Prince of Peace Abbey in Oceanside, California, in 1958.

When asked what kind of leader he was, Fr. Bonaventure humbly says, “I’m sure I wasn’t considered charismatic. I was just plodding along.”

He resigned as archabbot in 1966.

Throughout his years as a monk, Fr. Bonaventure has had a variety of duties in addition to being archabbot. He was a teacher, a missionary in Peru and helped lead monasteries in the interim in Mexico and the U.S. He also had stints leading several parishes before returning to St. Meinrad where he has helped with projects in the archabbey’s development office.

Throughout all of his assignments, Fr. Bonaventure has always held true to the vows of a Benedictine monk — vows of obedience, stability and fidelity to the monastic way of life.

He does quite a bit of Scripture study on the kingdom of God, although not nearly as much as he’d like because of vision problems. He says he spends most of his day praying the Divine Office, which he listens to on tape.

He attends coffee break with other monks at 10 o’clock every morning and attends Mass in the infirmary at 11:15 a.m., followed by lunch in the infirmary dining room. His afternoon includes a nap and some free time. Sometimes he prays or listens to audiobooks.

He also has an iPad and catches up with friends and family on Facebook. On March 27, he said he had just sent his niece a message on Facebook the day before wishing her a happy birthday.

After 5 o’clock, he likes to watch the local news, especially the weather forecast. He used to watch Carol Burnett shows, but says he now watches a lot of CNN. He once enjoyed long walks, but is now confined to a wheelchair.

Just like his interests, Fr. Bonaventure has noticed several changes in the Catholic faith over the course of his eight decades as a monk, including the lack of “a greater interest and attention to the life of Sunday Mass.” It didn’t used to be that way, he says.

“My grandma had 10 children and her husband died from typhoid fever when she was pregnant with the youngest,” he says. “She got the kids in the wagon and got the kids to Mass a couple miles on Sunday. I don’t remember a Sunday my father didn’t take me and my brothers to Sunday Mass.”

He longs for more people to follow St. Benedict’s teaching’s.

“St. Benedict starts out with things to observe,” he says. “First, love God with all your heart and strength. Love your neighbors as you are. It has to get simpler more than complicated in life.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THE ADVENTURE OF OBEDIENCE...

By Sean Gallagher

August 16, 2013

ST. MEINRAD—“When you make the vow of obedience, you don’t know what’s going to happen.”

That was how retired Benedictine Arch-abbot Bonaventure Knaebel of Saint Meinrad Archabbey in St. Meinrad succinctly summarized his 75 (80) years as a monk and 70 (75) years as a priest.

Born in 1918 in New Albany, he professed his monastic vows during the Great Depression in 1938, was ordained a priest at the height of World War II in 1943 and elected Archabbot of Saint Meinrad in 1955, eventually resigning from the office in 1966.

During his 75 (80) years as a monk, Archabbot Bonaventure has also served as a seminary instructor, a missionary in Peru, temporary administrator of monasteries in Mexico and the United States, chaplain of St. Paul Hermitage in Beech Grove and pastor or administrator of three parishes in the Archdiocese of Indianapolis.

It was to all of these places and these wide and varied ministry experiences that Arch-abbot Bonaventure’s fidelity to his vow of obedience led him.

Benedictine Arch-abbot Justin DuVall, Saint Meinrad’s then current leader, admires his predecessor’s dedication to obedience.

“He is one of the most obedient monks, really, in a way, that I know,” Arch-abbot Justin said. “He’s the kind of guy who, as abbot or when I was prior, I could ask him, ‘Could you do this?’ or ‘I need this to be done,’ and he’d say ‘Certainly.’ He would do it.”

Archabbot Bonaventure’s adventure of obedience started while growing up in New Albany.

Discerning his calling early on

The Arch-abbot showed an interest in the priesthood when he was in the seventh grade at the former Holy Trinity School in New Albany after a man from Holy Trinity Parish had been ordained a priest.

He explored that desire in part by serving at daily Mass at the parish—a Mass that started at 6 a.m. In response to this desire to be an altar server, his mother bought him an alarm clock.

“That was her way of seeing how true the idea was,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said. “Was it just a fleeting thing or is it steady? I must have walked there. It was more than a mile away. If there was snow on the ground, I could take a street car.”

When he completed eighth grade, he decided to enter the minor seminary at Saint Meinrad. Once he got there, though, he soon yearned to be back home. A monk on the seminary staff helped him through this difficult time.

“The main thing that he did that was a lifesaver was he got in touch with my folks, and told them not to come down to visit until the second Sunday in October … ,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said. “If they had come like two weeks after I got here, I would have gotten into the car and gone home with them.”

He was impressed enough by the monks and by reading a biography of St. Benedict that the next year he declared his intention to join the monastery when he was old enough.

From math teacher to Arch-abbot

Early on, his life in the monastery was much like many other young monks—receiving formation in the monastic life and for the priesthood in the seminary.

Ordained in 1943, he asked Benedictine Arch-abbot Ignatius Esser if he could serve as a military chaplain.

“But we already had six men as chaplains at the time,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure recalled. “So he didn’t take me up on it.”

He put his vow of obedience into action in accepting that decision. It was soon tested again when Benedictine Father Theodore Heck, then rector of the seminary, asked him to study mathematics in graduate school, even though his last math class was geometry as a high school sophomore.

“He didn’t ask me if I was interested in it,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said.

He earned a master’s degree in the field and nearly a doctorate, later teaching math in the minor seminary for eight years.

In 1955, Arch-abbot Ignatius announced his intention to resign after having led Saint Meinrad Archabbey for 25 years.

More than 100 monks participated in the election to choose his successor. Many ballots were cast before a monk received enough votes to be elected. As each ballot was counted, the name of the monk on it was announced.

During the counting of the last ballot, Arch-abbot Bonaventure, then only 38, said he “had butterflies” as he kept hearing his name called.

Much like a papal election, when he reached a majority on the ballots, he was asked if he accepted the election.

Arch-abbot Bonaventure consented “with the help of God” to become the leader of the monastery, treating the will of his fellow monks as another test of his vow of obedience.

“Certainly, it was expected of you at that time that if you were elected that you would accept it,” he said.

The challenge of leadership

The responsibilities that Arch-abbot Bonaventure took on after his election were wide and varied.

He initiated various projects as Arch-abbot, including the construction of the monastery’s first guest house, a water purification plant and two sewage ponds.

He laughed as he said that this last project was “the only successful thing I did.

“The guest house has been torn down. And the water [purification] plant is now the pottery shop.”

He and the monastic community also established two new monasteries during his tenure—Prince of Peace Abbey in Oceanside, Calif., and San Benito Priory in Huaraz, Peru.

The latter came in response to the call of Blessed John XXIII in 1961 to religious communities in the United States to send 10 percent of their members to minister in Central and South America within 10 years.

Arch-abbot Bonaventure and the monks of Saint Meinrad obeyed and established their foothold in Peru less than a year after the pope laid down the challenge. In addition to the priory, the monks ministering there also operated a minor seminary in Huaraz, which is located deep in the mountains of Peru.

While being responsible for various brick and mortar projects, Arch-abbot Bonaventure was also given the charge of caring for the souls of nearly 200 monks.

One of them was Benedictine Father Meinrad Brune, who became a novice the same year that Arch-abbot Bonaventure was elected.

One day, Arch-abbot Bonaventure heard Father Meinrad complaining about another monk. He later called him to his office and simply asked him to read an article on what he had done.

“He didn’t even discuss it with me,” Father Meinrad said. “It was a somewhat indirect way to give me correction. But he did it in a very thoughtful way. It was a very good article. And I knew right away exactly what he was referring to. So I thanked him for it, and that was all that was said.”

The Second Vatican Council also took place while Arch-abbot Bonaventure was the monastery’s leader. He was obedient to the will of the bishops at the council by starting the process to make the changes called for at Vatican II in the celebration of Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours (also known as the Divine Office or simply the Office).

“We did make some appropriate adjustments,” he said. “While the last section of the council was going on, we set up a liturgical committee and they started celebrating the Office in English as an experiment in the chapter room [a special meeting room in the monastery] while we were still doing it in Latin [in the Archabbey Church].”

The years that Arch-abbot Bonaventure served as leader of Saint Meinrad, however, included some trials as well. Nearly 50 years later, he still only talked about them in a measured manner.

“One of the older priests told someone, then I heard it, that Arch-abbot Ignatius enjoyed being abbot and Bonaventure doesn’t enjoy it that much,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said. “That was the impression that the older fellow had gotten. I think, in a sense, that must have been true.

“At the time [of my resignation in 1966], I said that Father Abbot Ignatius served for 25 years, but 11 years of what we’ve been having is like 25.”

Arch-abbot Justin reflected on the challenging time in which Arch-abbot Bonaventure served as leader of Saint Meinrad.

“You can’t be the abbot in another era than your own,” Arch-abbot Justin said. “When he was elected in 1955, who could have foreseen the council and the aftermath of that? And that’s when he was abbot. Those were challenging times not just for him or for Saint Meinrad, but for the Church at large.”

Life as missionary

Arch-abbot Bonaventure stepped down as leader of Saint Meinrad in June 1966. By November of that year, he was studying Spanish in preparation to serve in Peru.

At first, he served as the rector of the minor seminary.

His ministry there changed dramatically, however, in 1970 when an earthquake struck the country. Some 70,000 people died in the quake, including Benedictine Father Bede Jamieson, prior of San Benito Priory at the time.

When the quake occurred, Arch-abbot Bonaventure was walking with a local bishop just prior to the blessing of a cornerstone for a new convent for a community of religious sisters.

“There were garden walls along there,” he said. “Then the earthquake came. Luckily, those walls didn’t fall down. If we had been walking in a narrow street in front of houses like they were in Huaraz, the fronts of the buildings would have fallen and hit people in the streets.”

Instead of assisting in relief work in Peru, Arch-abbot Bonaventure was asked to return to the United States to make mission appeals in parishes across the country. He later did this ministry full time from 1974-79.

Leading parishes, other monasteries

Beginning in the late 1970s, Arch-abbot Bonaventure began serving in a series of parish and monastic assignments, serving 17 years in parishes and at the St. Paul Hermitage in the archdiocese, and as temporary administrator in monasteries in Mexico, Wisconsin and Texas.

While in Mexico, he also tackled a good amount of parish ministry.

“I had to revive my Spanish. It was interesting work,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said. “I had plenty of Masses. I think I had three Holy Thursday Masses and three Easter Vigils [during one Holy Week].”

His last parish assignment before retiring to the monastery was at St. Michael Parish in Bradford. In 1997, its pastor, Father Bernard Koopman, died suddenly and Arch-abbot Bonaventure, 77 at the time, was asked to fill in for two and a half months until a pastor could be appointed.

He obeyed, thinking he would return to the monastery in short order. He ended up staying there for six years.

John Jacobi, St. Michael’s director of religious education while Arch-abbot Bonaventure led the parish, continues in that position today.

“He had a lot of energy,” Jacobi said. “He showed up at anything—youth events, deanery events and things like that. Being able to watch him as a younger person kept me moving. It was his love of the Church, his love of ministry what sustained him.”

Arch-abbot Bonaventure also helped Jacobi grow in his ministry.

“I think he was really good at knowing when to listen and when to put his two cents in,” Jacobi said. “I think he taught me how to be a good parish minister, how to approach people where they are. He was just really good at that.”

Arch-abbot Bonaventure stepped down from leading St. Michael Parish because of health problems. In the past 10 years, he has had both of his knees replaced and dealt with a liver ailment.

Today however, at 94, he continues periodically to celebrate Mass in Spanish at St. Mary Parish in Huntingburg, Ind., in the Evansville Diocese, and assists in projects in Saint Meinrad’s development office.

When asked to give words of encouragement to men considering life as a Benedictine monk, Arch-abbot Bonaventure spoke about the purpose of his adventure of obedience—growing closer to God.

“I’m not sure that you would have any of the experiences that I’ve had, but it is a fulfilling life,” Arch-abbot Bonaventure said. “It does help you to do what the Rule [of St. Benedict] says, to seek God.”